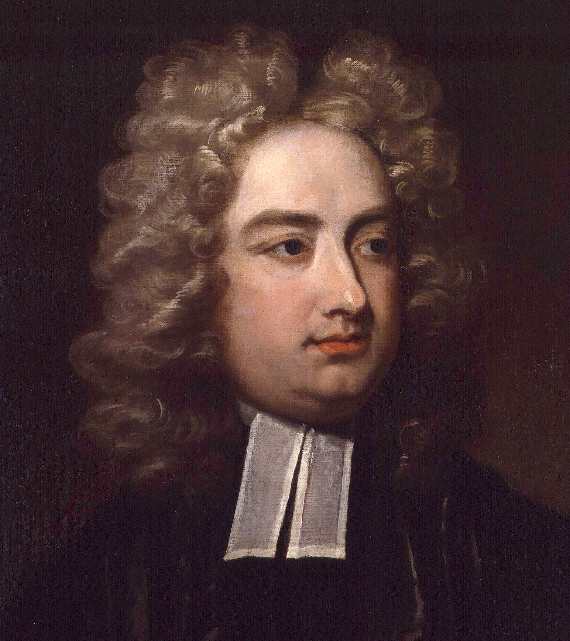

JONATHAN SWIFT

Portrait by Charles Jervas

Jonathan Swift was born in Dublin, on November 30, 1667 to an Anglo-Irish family. A man of religion, Swift received a Doctor of Divinity degree in 1702 from Trinity College in Dublin, and embarked on a career as a working member of the clergy of the Protestant, Church of Ireland. He rose to the rank of Dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin.

It is Swift’s work as a writer rather than his time on the pulpit for which he is best known. His writings encapsulate many genres: satire, essay, political pamphleteering, and poetry, though he less recognized for the latter.

Swift is most widely celebrated for his classic works such as A Modest Proposal, A Tale of a Tub, Gulliver's Travels, Drapier’s Letters and An Argument Against Abolishing Christianity. His name is synonymous with prose satire and he set the standard for this form in the English language.

The Swift family tree contains several literary branches, including poet John Dryden, Sir Walter Raleigh, Francis Godwin, and playwright and poet Sir William Davenant.

As Swift grew older, he developed an increasing interest in politics. The clergyman traveled to London in 1707 to try and persuade the Whig government of Lord Godolphin to extend to the Irish clergy the so called “Queen Anne’s Bounty”, a fund established in 1704 to augment the incomes of the poorer clergy of the Anglican rite.

Initially a Whig, he found greater support for his positions among the Tories, and eventually threw his weight and considerable writing talents behind the Tory cause. When a Tory government came to power in 1710, Swift was rewarded by being made a part of the Tory inner circle. He also assumed editorship of the pro-Tory newspaper The Examiner.

During the last years of his life the writer was plagued by maladies which placed a great strain on his physical and mental abilities. So much so that guardians were appointed to protect him and his estate from unscrupulous opportunists. He died in October 19, 1745.

We hope you enjoy these works by Jonathan Swift.

A Satirical Elegy

On the Death of a Late FAMOUS GENERAL

His Grace! impossible! what dead!

Of old age, too, and in his bed!

And could that Mighty Warrior fall?

And so inglorious, after all!

Well, since he's gone, no matter how,

The last loud trump must wake him now:

And, trust me, as the noise grows stronger,

He'd wish to sleep a little longer.

And could he be indeed so old

As by the news-papers we're told?

Threescore, I think, is pretty high;

'Twas time in conscience he should die.

This world he cumber'd long enough;

He burnt his candle to the snuff;

And that's the reason, some folks think,

He left behind so great a stink.

Behold his funeral appears,

Nor widow's sighs, nor orphan's tears,

Wont at such times each heart to pierce,

Attend the progress of his hearse.

But what of that, his friends may say,

He had those honours in his day.

True to his profit and his pride,

He made them weep before he dy'd.

Come hither, all ye empty things,

Ye bubbles rais'd by breath of Kings;

Who float upon the tide of state,

Come hither, and behold your fate.

Let pride be taught by this rebuke,

How very mean a thing's a Duke;

From all his ill-got honours flung,

Turn'd to that dirt from whence he sprung.

The Progress of Poetry

The Farmer's Goose, who in the Stubble,

Has fed without Restraint, or Trouble;

Grown fat with Corn and Sitting still,

Can scarce get o'er the Barn-Door Sill:

And hardly waddles forth, to cool

Her Belly in the neighb'ring Pool:

Nor loudly cackles at the Door;

For Cackling shews the Goose is poor.

But when she must be turn'd to graze,

And round the barren Common strays,

Hard Exercise, and harder Fare

Soon make my Dame grow lank and spare:

Her Body light, she tries her Wings,

And scorns the Ground, and upward springs,

While all the Parish, as she flies,

Hear Sounds harmonious from the Skies.

Such is the Poet, fresh in Pay,

(The third Night's Profits of his Play;)

His Morning-Draughts 'till Noon can swill,

Among his Brethren of the Quill:

With good Roast Beef his Belly full,

Grown lazy, foggy, fat, and dull:

Deep sunk in Plenty, and Delight,

What Poet e'er could take his Flight?

Or stuff'd with Phlegm up to the Throat,

What Poet e'er could sing a Note?

Nor Pegasus could bear the Load,

Along the high celestial Road;

The Steed, oppress'd, would break his Girth,

To raise the Lumber from the Earth.

But, view him in another Scene,

When all his Drink is Hippocrene,

His Money spent, his Patrons fail,

His Credit out for Cheese and Ale;

His Two-Year's Coat so smooth and bare,

Through ev'ry Thread it lets in Air;

With hungry Meals his Body pin'd,

His Guts and Belly full of Wind;

And, like a Jockey for a Race,

His Flesh brought down to Flying-Case:

Now his exalted Spirit loaths

Incumbrances of Food and Cloaths;

And up he rises like a Vapour,

Supported high on Wings of Paper;

He singing flies, and flying sings,

While from below all Grub-street rings.

The Beasts' Confession

To the Priest, on Observing how most Men mistake their own

Talents

When beasts could speak (the learned say,

They still can do so ev'ry day),

It seems, they had religion then,

As much as now we find in men.

It happen'd, when a plague broke out

(Which therefore made them more devout),

The king of brutes (to make it plain,

Of quadrupeds I only mean)

By proclamation gave command,

That ev'ry subject in the land

Should to the priest confess their sins;

And thus the pious wolf begins:

"Good father, I must own with shame,

That often I have been to blame:

I must confess, on Friday last,

Wretch that I was! I broke my fast:

But I defy the basest tongue

To prove I did my neighbour wrong;

Or ever went to seek my food

By rapine, theft, or thirst of blood."

The ass, approaching next, confess'd

That in his heart he lov'd a jest:

A wag he was, he needs must own,

And could not let a dunce alone:

Sometimes his friend he would not spare,

And might perhaps be too severe:

But yet, the worst that could be said,

He was a wit both born and bred;

And, if it be a sin or shame,

Nature alone must bear the blame:

One fault he hath, is sorry for't,

His ears are half a foot too short;

Which could he to the standard bring,

He'd show his face before the King:

Then for his voice, there's none disputes

That he's the nightingale of brutes.

The swine with contrite heart allow'd,

His shape and beauty made him proud:

In diet was perhaps too nice,

But gluttony was ne'er his vice:

In ev'ry turn of life content,

And meekly took what fortune sent:

Inquire through all the parish round,

A better neighbour ne'er was found:

His vigilance might some displease;

'Tis true he hated sloth like peas.

The mimic ape began his chatter,

How evil tongues his life bespatter:

Much of the cens'ring world complain'd,

Who said, his gravity was feign'd:

Indeed, the strictness of his morals

Engag'd him in a hundred quarrels:

He saw, and he was griev'd to see't,

His zeal was sometimes indiscreet:

He found his virtues too severe

For our corrupted times to bear:

Yet, such a lewd licentious age

Might well excuse a Stoic's rage.

The goat advanc'd with decent pace;

And first excus'd his youthful face;

Forgiveness begg'd that he appear'd

('Twas nature's fault) without a beard.

'Tis true, he was not much inclin'd

To fondness for the female kind;

Not, as his enemies object,

From chance, or natural defect;

Not by his frigid constitution,

But through a pious resolution;

For he had made a holy vow

Of chastity as monks do now;

Which he resolv'd to keep for ever hence,

As strictly too, as doth his Reverence.

Apply the tale, and you shall find,

How just it suits with human kind.

Some faults we own: but, can you guess?

Why?--virtues carried to excess,

Wherewith our vanity endows us,

Though neither foe nor friend allows us.

The lawyer swears, you may rely on't,

He never squeez'd a needy client;

And this he makes his constant rule,

For which his brethren call him fool:

His conscience always was so nice,

He freely gave the poor advice;

By which he lost, he may affirm,

A hundred fees last Easter term.

While others of the learned robe

Would break the patience of a Job;

No pleader at the bar could match

His diligence and quick dispatch;

Ne'er kept a cause, he well may boast,

Above a term or two at most.

The cringing knave, who seeks a place

Without success, thus tells his case:

Why should he longer mince the matter?

He fail'd because he could not flatter;

He had not learn'd to turn his coat,

Nor for a party give his vote:

His crime he quickly understood;

Too zealous for the nation's good:

He found the ministers resent it,

Yet could not for his heart repent it.

The chaplain vows he cannot fawn,

Though it would raise him to the lawn:

He pass'd his hours among his books;

You find it in his meagre looks:

He might, if he were worldly wise,

Preferment get and spare his eyes:

But own'd he had a stubborn spirit,

That made him trust alone in merit:

Would rise by merit to promotion;

Alas! a mere chimeric notion.

The doctor, if you will believe him,

Confess'd a sin; and God forgive him!

Call'd up at midnight, ran to save

A blind old beggar from the grave:

But see how Satan spreads his snares;

He quite forgot to say his prayers.

He cannot help it for his heart

Sometimes to act the parson's part:

Quotes from the Bible many a sentence,

That moves his patients to repentance:

And, when his med'cines do no good,

Supports their minds with heav'nly food,

At which, however well intended,

He hears the clergy are offended;

And grown so bold behind his back,

To call him hypocrite and quack.

In his own church he keeps a seat;

Says grace before and after meat;

And calls, without affecting airs,

His household twice a day to prayers.

He shuns apothecaries' shops;

And hates to cram the sick with slops:

He scorns to make his art a trade;

Nor bribes my lady's fav'rite maid.

Old nurse-keepers would never hire

To recommend him to the squire;

Which others, whom he will not name,

Have often practis'd to their shame.

The statesman tells you with a sneer,

His fault is to be too sincere;

And, having no sinister ends,

Is apt to disoblige his friends.

The nation's good, his master's glory,

Without regard to Whig or Tory,

Were all the schemes he had in view;

Yet he was seconded by few:

Though some had spread a hundred lies,

'Twas he defeated the Excise.

'Twas known, though he had borne aspersion,

That standing troops were his aversion:

His practice was, in ev'ry station,

To serve the King, and please the nation.

Though hard to find in ev'ry case

The fittest man to fill a place:

His promises he ne'er forgot,

But took memorials on the spot:

His enemies, for want of charity,

Said he affected popularity:

'Tis true, the people understood,

That all he did was for their good;

Their kind affections he has tried;

No love is lost on either side.

He came to Court with fortune clear,

Which now he runs out ev'ry year:

Must, at the rate that he goes on,

Inevitably be undone:

Oh! if his Majesty would please

To give him but a writ of ease,

Would grant him licence to retire,

As it hath long been his desire,

By fair accounts it would be found,

He's poorer by ten thousand pound.

He owns, and hopes it is no sin,

He ne'er was partial to his kin;

He thought it base for men in stations

To crowd the Court with their relations;

His country was his dearest mother,

And ev'ry virtuous man his brother;

Through modesty or awkward shame

(For which he owns himself to blame),

He found the wisest man he could,

Without respect to friends or blood;

Nor ever acts on private views,

When he hath liberty to choose.

The sharper swore he hated play,

Except to pass an hour away:

And well he might; for, to his cost,

By want of skill he always lost;

He heard there was a club of cheats,

Who had contriv'd a thousand feats;

Could change the stock, or cog a die,

And thus deceive the sharpest eye:

Nor wonder how his fortune sunk,

His brothers fleece him when he's drunk.

I own the moral not exact;

Besides, the tale is false in fact;

And so absurd, that could I raise up

From fields Elysian fabling Aesop;

I would accuse him to his face

For libelling the four-foot race.

Creatures of ev'ry kind but ours

Well comprehend their natural pow'rs;

While we, whom reason ought to sway,

Mistake our talents ev'ry day.

The ass was never known so stupid

To act the part of Tray or Cupid;

Nor leaps upon his master's lap,

There to be strok'd, and fed with pap,

As Aesop would the world persuade;

He better understands his trade:

Nor comes, whene'er his lady whistles;

But carries loads, and feeds on thistles.

Our author's meaning, I presume, is

A creature bipes et implumis;

Wherein the moralist design'd

A compliment on human kind:

For here he owns, that now and then

Beasts may degenerate into men.